Four Android emulators, two apps

So far the KB hasn’t actively pursued the preservation of mobile apps. However, born-digital publications in app-only form have become increasingly common, as well as “hybrid” publications, with apps that are supplemental to traditional (paper) books. At the request of our Digital Preservation department, I’ve started some exploratory investigations into how to preserve mobile apps in the near future. The 2019 iPres paper on the Acquisition and Preservation of Mobile eBook Apps by the British Library’s Maureen Pennock, Peter May and Michael Day provides an excellent starting point on the subject, and it highlights many of the challenges involved.

Before we can start archiving mobile apps ourselves, some additional aspects need to be addressed in more detail. One of these is the question of how to ensure long-term access. Emulation is the obvious strategy here, but I couldn’t find much information on the emulation of mobile platforms within a digital preservation context. In this blog post I present the results of some simple experiments, where I tried to emulate two selected apps. The main objective here was to explore the current state of emulation of mobile devices, and to get an initial impression of the suitability of some existing emulation solutions for long-term access.

For practical reasons I’ve limited myself to the Android platform1. Attentive readers may recall I briefly touched on this subject back in 2014. As much of the information in that blog post has now become outdated, this new post presents a more up-to date investigation. I should probably mention here that I don’t own or use any Android device, or any other kind of smartphone or tablet for that matter2. This probably makes me the worst possible person to evaluate Android emulation, but who’s going to stop me trying anyway? No one, that’s who!

Android emulation options

The Emulation General Wiki gives a good overview of Android emulators. Most of these are closed-source, and the Wiki warns that some may come with malicious apps pre-installed. For the purposes of long-term preservation and acccess, open-source solutions are much more relevant. The Wiki lists the following open-source emulators:

- Android-x86 is a port of the Android open source project to the x86 architecture. It is not an emulator, but rather an operating system that can be installed on either a physical device, or within a virtual machine (e.g. using VirtualBox or QEMU).

- Android Emulator is part of Android Studio, Google’s offial development environment for Android. Android Emulator “simulates Android devices on your computer so that you can test your application on a variety of devices and Android API levels without needing to have each physical device”.

- Anbox is “a container-based approach to boot a full Android system on a regular GNU/Linux system like Ubuntu”.

- Shashlik is another project for running Android apps on Linux.

It’s worth pointing out that most of these solutions aren’t really “emulators” in a strict sense. Android-x86 is an operating system can be run inside a virtual machine (without the need for real hardware emulation) on x86-based platforms. Android Emulator can do full ARM hardware emulation, but is usually run with x86 system images. Anbox is not an emulator at all, but rather a compatibility layer, similar to how WINE allows one to run Windows applications on Unix-like operating systems. Shashlik uses a hybrid approach, by pairing a stripped-down Android base that is run within a modified version of QEMU with graphics rendering on the host machine3. For the sake of simplicity, I will use the term “emulation” for all of the above in this post.

Test setup

The experiments described in the remainder of this post focus on the emulation of two selected test apps:

- ARize is an “augmented reality” app. It is used, among other things, to add 3-D visualizations and animations to the Dutch-language children’s book “De avonturen van Max - Op zoek naar F…”.4.

- Immer is a book reading app that claims to “help[ing] you read more often, easily and enjoyably on your phone or tablet”.

I tried to emulate these apps using the following emulated environments:

- Android-x86, running in VirtualBox

- Android-86, running in QEMU

- Anbox

- Android Emulator (Android Studio)

I did not include Shashlik, as this project has been inactive since 2016. I evaluated each of the emulations by the following (admittedly crude and incomplete) criteria:

- Does the emulated environment work at all?

- Is it possible to install the ARize and Immer apps?

- Do the installed apps work?

I ran all tests on a regular desktop PC with the following characteristics:

- Quad-core Intel Core i5-6500 processor

- 12 GB RAM

- Operating system: Linux Mint 19.3 (Tricia)

Below follows a more detailed discussion of each of the emulated environments. I deliberately included quite a lot of detail here, mostly to make life easier for others who may want to do similar tests themselves. If you’re only interested in the main findings, you may want to skip these details and head right over to the “Summary and conclusions” section.

Android-x86 + VirtualBox

Setup

This blog post by Sjoerd Langkemper gives a good overview of how to set up a virtual machine running Android-x86 with VirtualBox, and I largely followed the instructions mentioned here. I used VirtualBox verion 6.0.24, r139119. I had some difficulty getting a functional virtual machine from the latest Android-86 ISO installer image, so in the end I settled for the pre-built VirtualBox image from osboxes.org (Android-x86 9.0-R2, 64-bit). Initially the virtual machine got stuck on a black screen at startup. I was able to fix this by setting the graphics controller (which can be found under “Display” in the VM settings) to “VBoxSVGA”. I also set the number of processors (“System” settings, “Processor” tab) to 2, as according to the Android-86 documentation:

Processor(s) should be set above 1 if you have more than one virtual processor in your host system. Failure to do so means every single app (like Google Chrome) might crush if you try to use it.

Here’s what the virtual machine looks like after it has booted:

At a first glance, everything pretty much works, although I did run into a number of crashes of the Chrome browser app. These all occurred while entering text into the address bar. Strangely, I couldn’t replicate these crashes in a later session, so I’m not sure about the exact cause.

App installation

To install apps on Android, one would normally use the Google Play Store. Within a typical preservation workflow, you’re more likely to have a local copy of the app’s Android Package (APK). Because of this, I tried to “emulate” this by using locally downloaded APKs for my experiments. To achieve this, I first used the gplaycli tool to download APK files of the test apps to my local (Linux) machine. Installing locally downloaded APKs on an emulated Android machine can be a bit tricky, as VirtualBox (and most other Android emulators) provides no easy way to set up shared folders between the host machine and the emulated device. The easiest method (which works for all of the environments covered by this post) uses the Android Debug Bridge (adb), which is part of Android Studio. Langkemper’s blog post covers the use of the adb tool in detail, so for brevity I’ll only show the basic steps here.

First, we need to find the IP address of our virtual Android machine, which in my particular case turned out to be “127.0.0.1” (localhost)5. Then we can use the Android Debug Bridge tool to connect to the virtual machine:

adb connect 127.0.0.1

If all goes well, you should see this:

connected to 127.0.0.1:5555

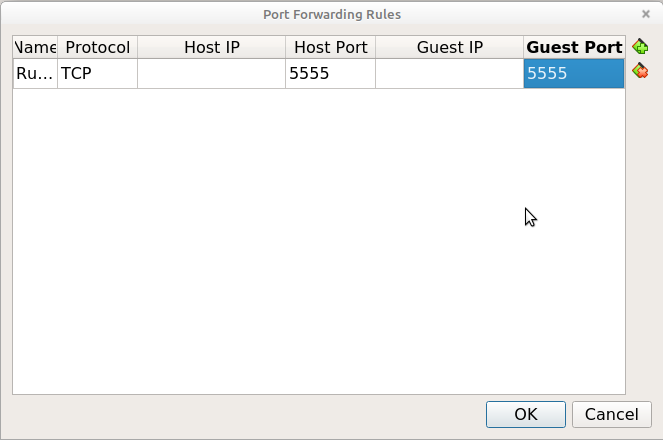

If you get a “Connection refused” error instead, you might need to set a port forwarding rule for the virtual machine. In VirtualBox, go to “Network” in your VM’s settings. Click on “Advanced”, followed by “Port Forwarding”. Here, click on the green “+” icon (top-right). This adds a port forwarding rule. Now change the values of both “Host Port” and “Guest Port” to 5555 (defaults for both are 0):

Then try to connect again. Once the connection is established, you can install the local APK file with adb using its “install” subcommand, with the name of the package file as an argument:

adb install com.Triplee.TripleeSocial.apk

Results for test apps

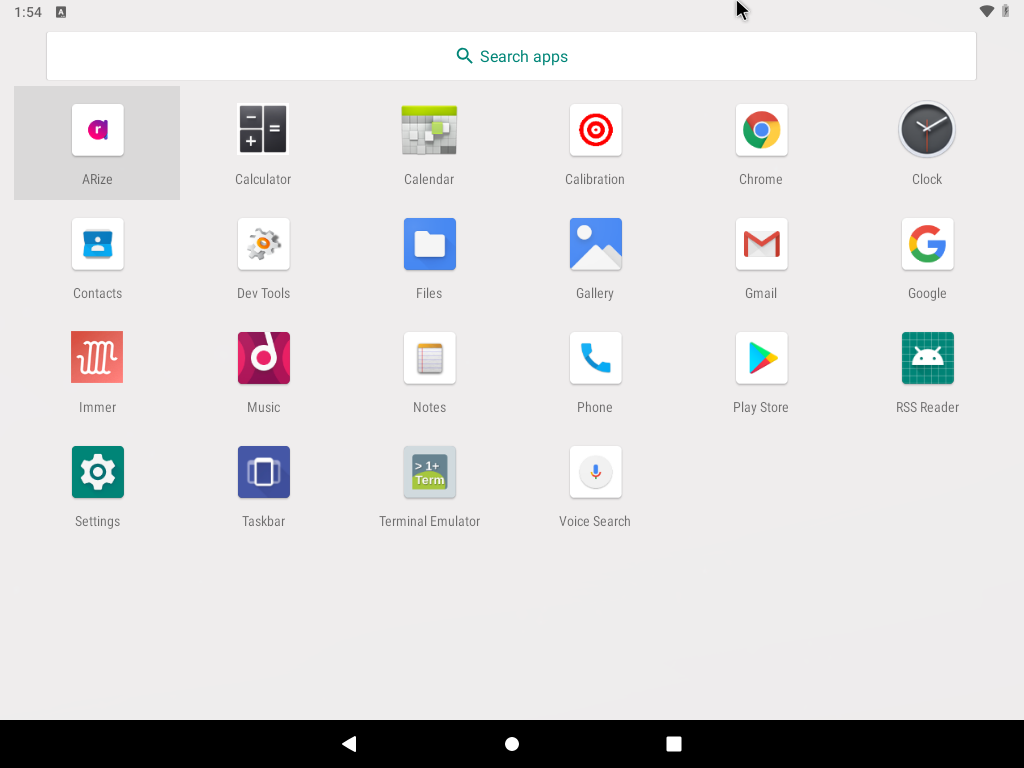

I was able to install the test apps without any problems, and their launcher icons showed up promptly after the installation:

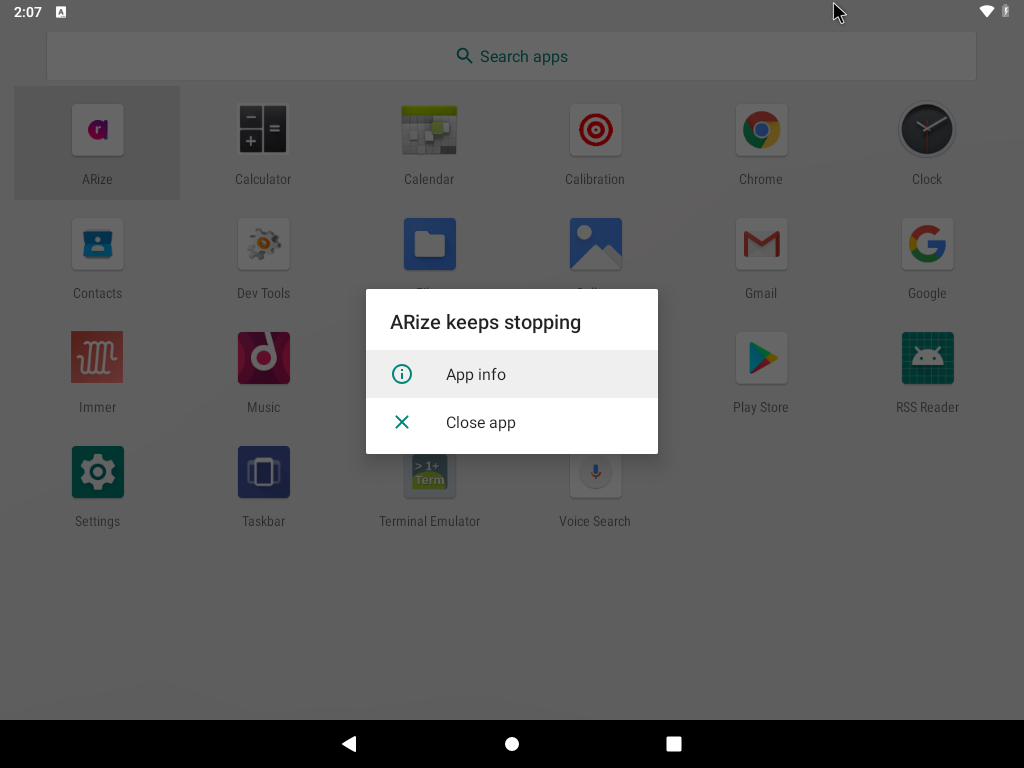

However, the ARize app crashed immediately after being launched:

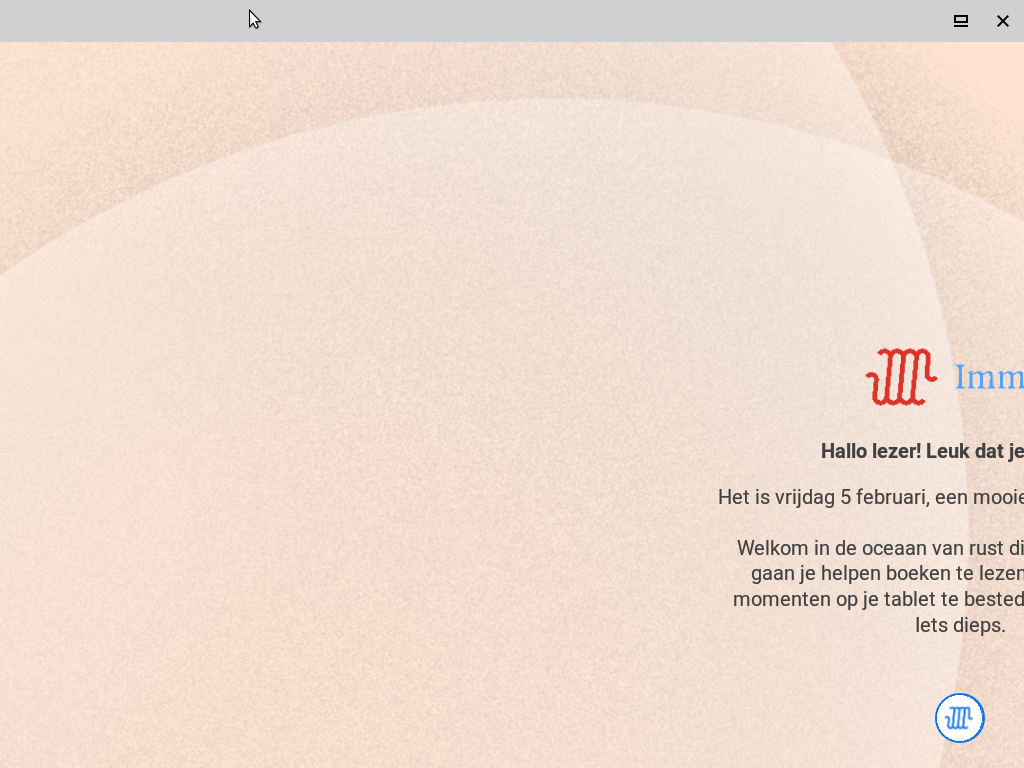

By contrast, the Immer app worked without any problems. Below are some screenshots that show Immer in action:

Android-x86 + QEMU

Setup

Since the Debian packages of QEMU for the Linux Mint version I’m using are way out of date, I first compiled and installed the most recent (5.2) QEMU release from its source, using the instructions here6. For setting up Android-x86 within QEMU, I largely followed this guide by Nitesh Kumar (starting from the Android-x86 QEMU Installation Walkthrough section). However, these instructions initially failed for me, and I could trace this back to problems with QEMU’s OpenGL (which is related to graphics rendering) support7. After some experimentation, I managed to make it work by removing all OpenGL-related command line arguments. I’ll briefly summarize the setup steps here:

- Download the Android-x86 ISO installer image from here (I picked the 64-bit 9.0 R2 release).

- Create a virtual hard disk (size: 8 GB):

qemu-img create -f qcow2 androidx86_9_hda.img 8G - Boot the Android-x86 live ISO image inside a virtual machine, attaching also the virtual hard disk:

qemu-system-x86_64 \ -enable-kvm \ -m 2048 \ -smp 2 \ -cpu host \ -device ES1370 -device virtio-mouse-pci -device virtio-keyboard-pci \ -serial mon:stdio \ -boot menu=on \ -net nic \ -net user,hostfwd=tcp::4444-:5555 \ -hda androidx86_9_hda.img \ -cdrom android-x86_64-9.0-r2.iso - Follow Kumar’s guide (starting from the first screenshot) to install Android on the virtual machine.

- After the installation process is completed, close down the virtual machine (you can do this by simply closing the QEMU window), and then re-start it using (same command as before, but omitting the

-cdromargument):qemu-system-x86_64 \ -enable-kvm \ -m 2048 \ -smp 2 \ -cpu host \ -device ES1370 -device virtio-mouse-pci -device virtio-keyboard-pci \ -serial mon:stdio \ -boot menu=on \ -net nic \ -net user,hostfwd=tcp::4444-:5555 \ -hda androidx86_9_hda.img

And here’s what this looks like after start-up::

One oddity is that the rendering of colours doesn’t look quite right, with reds shown as shades of blue (this is even more apparent when you open some web pages with the Chrome app). Perhaps this could be remedied by using better device settings in QEMU, but I haven’t looked into this any further.

App installation

Because of the slightly different network configuration, I had to add a reference to the 4444 network port make to make the adb connection to the QEMU machine:

adb connect 127.0.0.1:4444

After this, the package install procedure is identical to the one I showed for VirtualBox8.

Results for test apps

I was able to install both test apps without problems on the QEMU machine. As with VirtualBox, the ARize app consistently crashed after launch. The Immer app worked without any issues.

Anbox

Setup

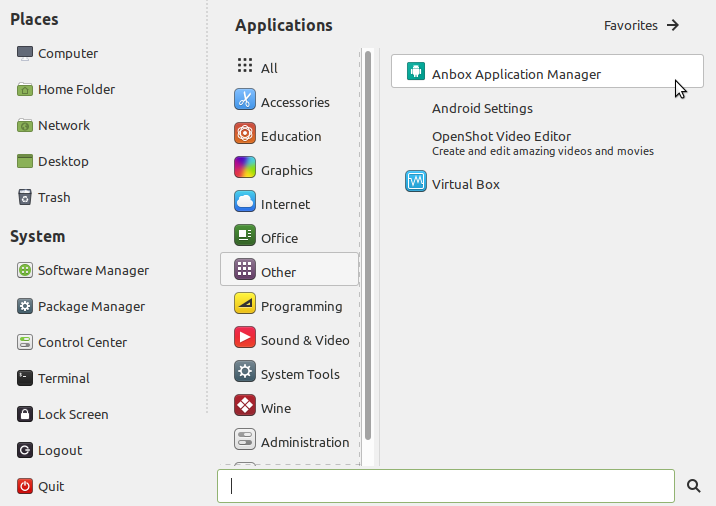

I installed Anbox (version 4-56c25f1) by following the official Anbox documentation. After the installation, fire up the “Anbox Application Manager” from (depending on your Linux desktop) the desktop menu or launch bar9:

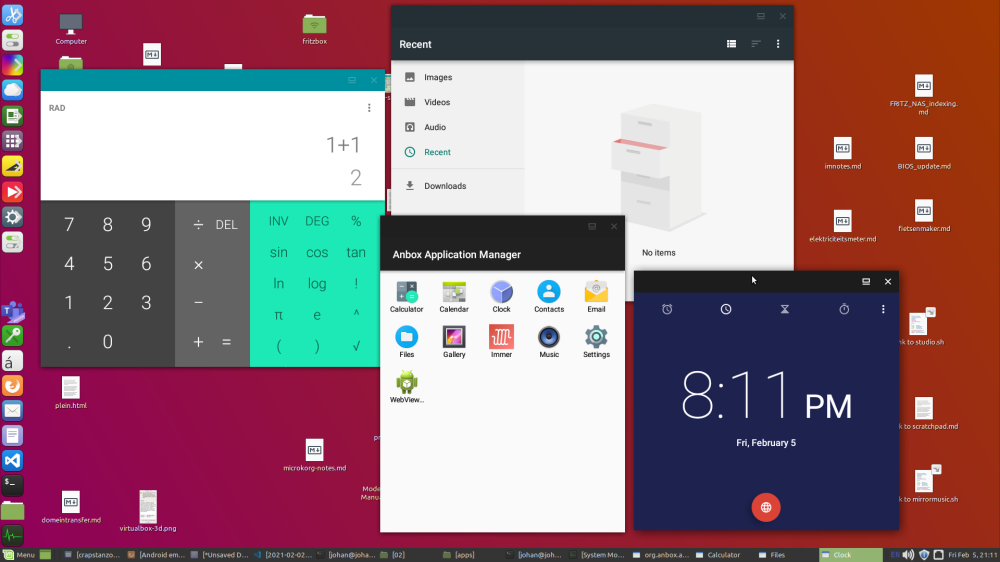

Unlike the other platforms covered in this post, Anbox doesn’t try to “emulate” a single device, but rather provides a compatibility layer that allows you to run Android apps from the Application Manager. Each app is launched in its own window, as shown below:

Looking at the information under Settings, the current Anbox release is based on Android 7.1.1, which is quite an old version. A quick test with the pre-installed Webview Browser showed Anbox couldn’t connect to the internet, which apparently is a known issue. After some searching I found a workaround here. I simply ran the following command:

nmcli con add type bridge ifname anbox0 -- connection.id \

anbox-net ipv4.method shared ipv4.addresses 192.168.250.1/24

I then closed and re-started the Anbox Application Manager, after which internet connectivity was working properly.

App installation

The Anbox Application Manager automatically launches an ADB server process, so you don’t need to manually run adb connect. Other than that, you can use the regular adb install commands to install the APK files.

Results for test apps

My attempt to install the ARize app failed with this error message:

adb: failed to install com.Triplee.TripleeSocial.apk:

Failure [INSTALL_FAILED_NO_MATCHING_ABIS: Failed to extract native libraries, res=-113]

According to this StackOverflow answer, this error can occur if an app uses native (e.g. ARM) libraries that are not compatible with the architecture of the (virtual) destination machine.

The Immer app installed without any problems, and I was also able to launch it. However, the text in the app is partially rendered outside the app window:

After I tried to re-size or maximize the app window, all text disappeared altogether. I was also unable to get the core book selection and reading functionality working (I just ended up with an empty screen), although clicking on the icon at the bottom did allow me to open and edit the app’s user profile.

Android Emulator (Android Studio)

Setup

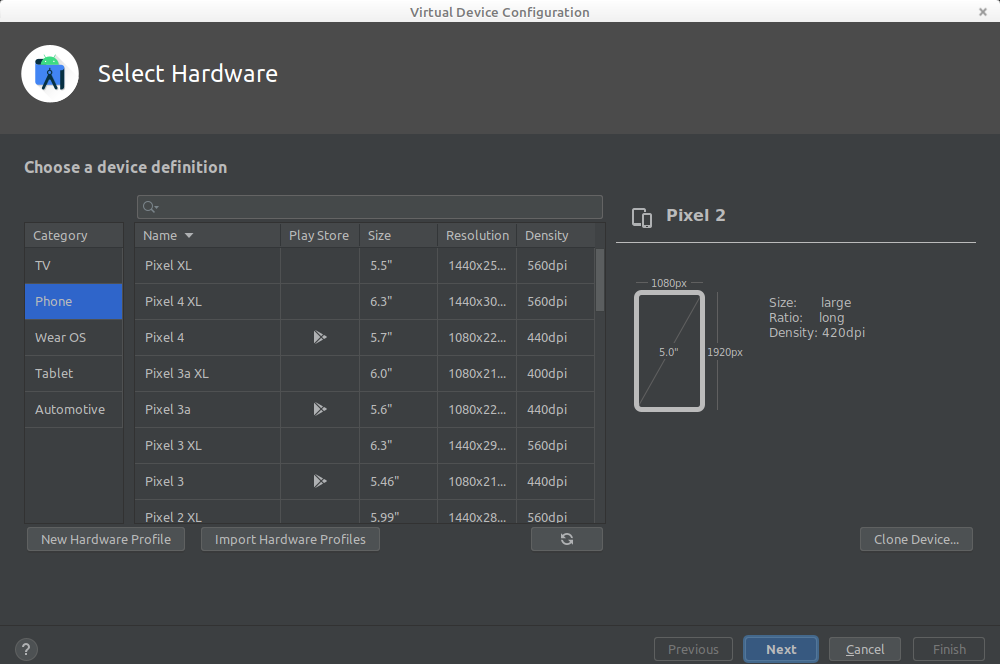

I installed Android Studio 4.1.2, which includes version 30.3.5.0 of Android Emulator. The emulator can be accessed from the “Tools” menu in the main Android Studio application. Here, the “AVD Manager” allows you to set up one or more Android Virtual Devices, each based on a user-specified “hardware profile, system image, storage area, skin, and other properties”. The setup process uses a wizard-like interface, which is pretty straightforward to use:

Nevertheless, it offers many customization options that allow you to mimic very specific device configurations. Both x86 and ARM system images are available for a variety of Android versions. The documentation advises against full ARM emulation because of the better performance of the x86 images. According the Emulator 30.0.0 release notes:

If you were previously unable to use the Android Emulator because your app depended on ARM binaries, you can now use the Android 9 x86 system image or any Android 11 system image to run your app – it is no longer necessary to download a specific system image to run ARM binaries. These Android 9 and Android 11 system images support ARM by default and provide dramatically improved performance when compared to those with full ARM emulation.

Because of this recommendation, I set up a device with Android 9 (for better comparison with the Android-86 tests) using the x86 image. The emulator can then be launched from either Android Studio, or using the command line. On startup, the emulated device looks like this:

Unlike the previous Android-x86 emulations, which are based on the Android Open Source Project, Android Emulator uses the official system images by Google. As a result, the “look and feel” of the Android Emulator virtual devices is quite different, and they also come with a larger number of pre-installed apps. Because of this, Android Emulator most likely approximates the Android experience on a physical device more closely10.

App installation

Like Anbox, Android Emulator automatically launches an ADB server process, so there’s no need to manually run adb connect. Installing APK files involves the usual adb install commands.

Results for test apps

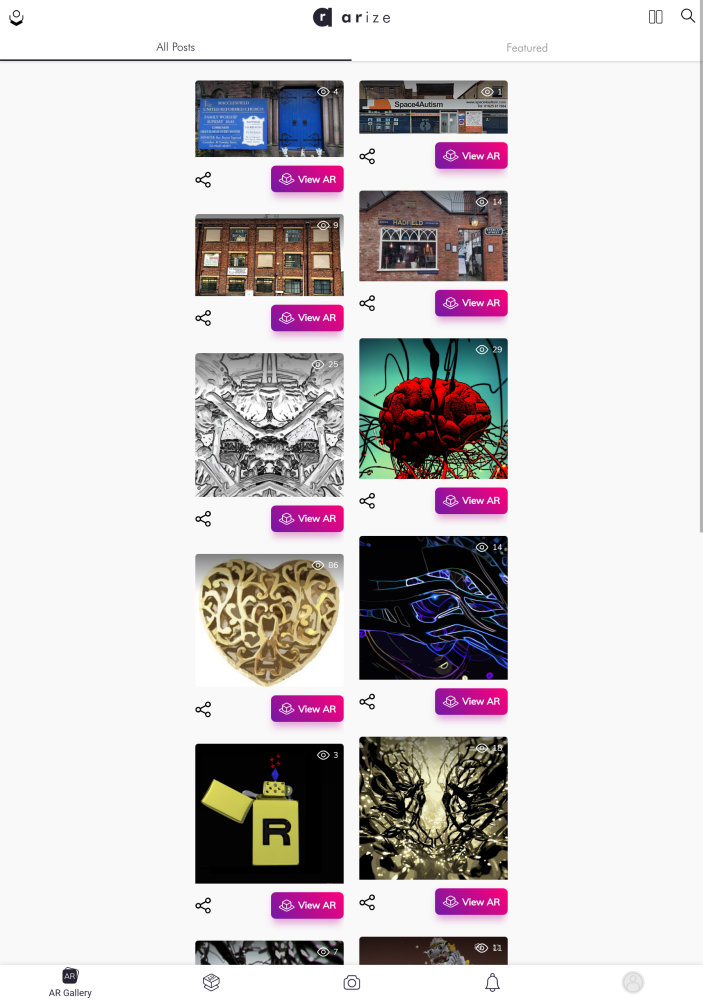

Both the ARize and Immer apps installed without any problems. Unlike all other emulators in this test, I was able to run the ARize app, although with some limitations. The screenshot below shows the app’s “gallery” screen:

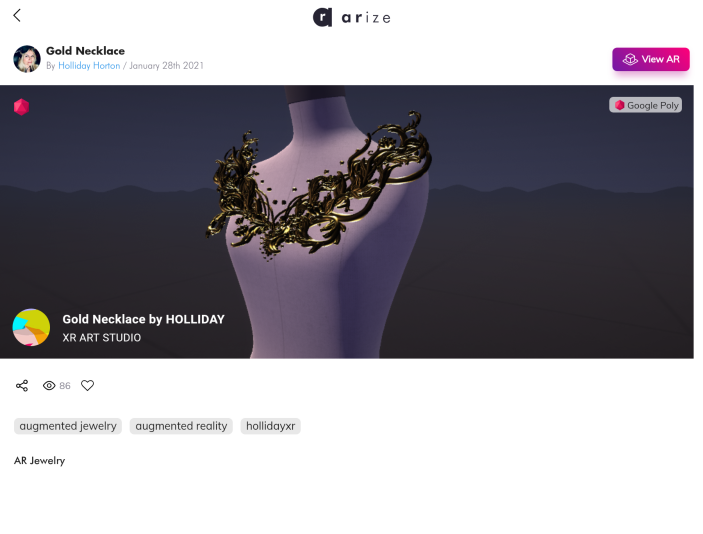

Clicking on an item in the gallery opens up a 3-D model, that can be manipulated by the user. As an example, here’s a model of a necklace:

If I understand it correctly, clicking the “View AR” button should switch the app to “augmented reality” mode, where the 3-D model is combined with video from the phone’s camera. Although Android Emulator allows one to attach external cameras (in my case a webcam), this didn’t quite work for me, with the emulator reporting a warning11. Whenever I tried to use the camera, the app showed a blank screen, after which the emulated device became unresponsive.

The Immer app worked without any issues, as shown in the screenshot below:

Although far from perfect, these Android Emulator results still look promising, bearing in mind that none of the other tested emulators could even run the ARize app at all.

Summary and discussion of results

The table below summarizes the main results of the emulation tests:

| Android-x86, VirtualBox | Android-x86, QEMU | Anbox | Android Studio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emulator version | 6.0.24, r139119 | 5.2 | 4-56c25f1 | 30.3.5.0 |

| Android version | Android-x86 9.0-R2 (64-bit) | Android-x86 9.0-R2 (64-bit) | Customized system image based on v. 7.1.1 of Android Open Source Project | Android 9.0 x86 system image (Google), API level 28 |

| Emulation approach | Virtualization | Virtualization | Compatibility layer | Virtualization (full ARM emulation optional, depending on system image) |

| ARize app installs | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| ARize app works | No | No | - | Partially (camera device not recognised; emulator unresponsive after using camera) |

| Immer app installs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Immer app works | Yes | Yes | Partially (rendering and navigation issues) | Yes |

It is important to stress that the tests presented here are limited in scope and size, and should not be interpreted as representative of Android apps in general. With that in mind, it is possible to draw some tentative conclusions.

Android-x86 limitations

First of all, the results suggest that emulation approaches based on Android-x86 may have some serious limitations. Going by various reports I found on sites like StackOverflow, the ARize app crashing on startup might be indicative of a more widespread problem. Sjoerd Langkemper mentions in his blog post that:

Testing on a virtual machine (VM) has some disadvantages. Testing on an actual Android phone is more reliable. Android is meant to run on ARM phones and not on x86 virtual machines, so things may randomly break when using a VM. Apps that ship with native libraries may not run at all in the VM, or they may run perfectly but don’t show up in the Play store.

A similar explanation, citing the use of native ARM libraries that are not supported by Android-x86, is given here. I’m not sure this is the culprit here, but if correct, this would seriously limit the usefulness of Android-x86 for long-term access.

Anbox

In its current form, Anbox seems of limited value for long-term access. With that said, I quite like its approach to providing access to Android apps, which is very different to the other emulators covered by this post. The project has an active developer community, and I’m curious how it will will develop in the future.

Android Emulator for long-term access

By contrast, Android Emulator (from Android Studio) could be a very interesting solution for emulating Android apps. It is the only emulator that was able to run both test apps (although with some issues in case of the ARize app). It also has an overall look and feel that is more faithful to a physical Android device. It’s worth pointing out here that under the hood, Android Emulator uses (a modified version of) QEMU12. Right now I’m unable to judge whether Android Emulator would be truly suitable as a solution for long-term access. Some concerns:

-

Google has developed it for the sole purpose of allowing Android developers to test their apps on a variety of (virtual) devices. It’s unlikely that Google will keep developing or maintaining it beyond Android’s lifetime. For long-term access, this implies that some organization should take over the maintenance of (a fork of) the software from that point onwards (assuming this is allowed under its licensing conditions, but see below).

-

The Terms and conditions of the Android Software Development Kit (of which Android Emulator is a part) state that:

3.1 Subject to the terms of the License Agreement, Google grants you a limited, worldwide, royalty-free, non-assignable, non-exclusive, and non-sublicensable license to use the SDK solely to develop applications for compatible implementations of Android.

and:

3.2 You may not use this SDK to develop applications for other platforms (including non-compatible implementations of Android) or to develop another SDK. You are of course free to develop applications for other platforms, including non-compatible implementations of Android, provided that this SDK is not used for that purpose.

To my legally untrained eyes, this appears to rule out the use of any of the components of the Android SDK for preservation and long-term access.

-

Also, Android Studio’s licensing information mentions that it includes “proprietary code subject to [a] separate license”. It’s not clear to me if this affects the Emulator component. The emulator’s subdirectory contains an additional +3000-line file with licensing information that applies specifically to the emulator component. I haven’t gone through it in detail (and am not planning to do so), but the licensing situation does look somewhat complex.

I can’t really assess to what extent this may impact the (future) use of Android Emulator as a long-term access solution, but I’d be interested in the opinion of any legal experts who may be reading this.

External dependencies

On a final note, it’s important to stress that the ability to run an app in an emulated environment is only one part of the preservation puzzle, and by itself it doesn’t guarantee its accessibility over time. As Pennock, May & Day write:

If the app is to be acquired in the most robust and complete form possible then we must find some way to deal with apps which have an inherent reliance on content hosted externally to the app. These are likely to lose their integrity over time, particularly as linkage to archived web content does not yet (if at all) appear to have become standard practice in apps.

This also applies to both the ARize and Immer apps, both of which rely on externally hosted content. To illustrate this, after disabling the internet connection on my PC, the ARize app showed this on start-up:

Immer simply started up with a blank screen. So, without (access to) the externally hosted resources, both apps are essentially useless.

Further resources

-

Considerations on the Acquisition and Preservation of Mobile eBook Apps

-

How to Run Android in QEMU to Play 3D Android Games on Linux

-

The proprietary nature of iOS severely constrains any emulation options; I may address this in a future blog post. ↩

-

As a matter of fact I’m still using this basic dumb phone, which I bough back in 2006. ↩

-

This instruction video shows how this works https://youtu.be/h4syCHftyCs. ↩

-

Finding the correct IP address can be a bit tricky. Langkemper’s blog suggests to either look at Android’s Wi-Fi preferences, or to run

ip aorifconfigin the Android terminal emulator app. However, in my case the value value shown in the Wi-Fi preferences is “10.0.2.15”, which is not recognised by adb. Theifconfigcommand reports 3 different entries (“wlan0”, “wifi_eth” and “lo”); eventually I found the value of the “lo” (“local loopback”) entry (“127.0.0.1”) did the trick. So you might need to experiment a bit to make things work. ↩ -

Compilation of QEMU requires Python Ninja package, so install this first by running

python3 -m pip install --user ninja. ↩ -

If you are connected to multiple devices at the same time, you’ll need to add the

-sswitch to your adb calls to specify the target device. See the documentation for details. ↩ -

This might seem obvious, but it’s not really clear from the documentation, so I thought I’d just mention it. ↩

-

But bear in mind I didn’t have any physical Android devices available while doing these tests. ↩

-

“Camera name ‘webcam0’ is not found in the list of connected cameras”. ↩

-

This “Under the hood of Android Emulator” Wiki entry shows how QEMU is used within the emulator (note that it hasn’t been updated since 2011, so it may be well out of date). ↩

Comments

Great post thank you Johan!

I thought I’d add a response to Pennock, May and Day’s comment that you quoted at the end:

“we must find some way to deal with apps which have an inherent reliance on content hosted externally to the app.”

The Emulation as a Service team at the University of Freiburg have started addressing this and gave a great presentation in collaboration with folks from the University of Amsterdam about this kind of thing at iPRES 2019 (direct download). While not directly addressing mobile apps/contexts the general approach of preserving and/or simulating obsolete web services and connecting them in emulation should be applicable to this use-case.

It would be interesting to explore the possibilities to integrate one of the tested emulators (preferably Android Emulator) in the Emulation as a Service framework. But the other challenge would be how a collection of Android apps would look like. I think currently no cultural heritage organizations is collecting mobile apps. So with the possibility of giving access to these app via emulation, we could develop a collection workflow for these kind of apps. What do we have to collect (file formats, metadata)?

For iOS apps it might be interesting that the new Macs are able to run iOS apps. Maybe this could lead to a working solution for preservation.

I believe the National Institute for Standards and Technology has been collecting apps in the National Software Reference Library (NSRL) and we may be able to access them in EaaSI. You can find lists of the Apps they have calculated hashes for here.

As part of the second round of EaaSI funding from the Sloan and Mellon foundations we committed to adding an Android emulator to EaaSI so this is on our agenda for the next 18 months, but currently is scheduled towards the end of that period.

Workflows are a challenge and question as part of that work, so any ideas related to that would be much appreciated. The EaaSI forum might be a good place to discuss those also, it’s open to all! (Johan posted about this topic there also, thank you Johan!)

@euanc Yes I remember seeing that presentation at iPres. Scalability will be an issue though, re-creating a complete server infrastructure for one app is one thing, but doing that for larger collections of apps is something else. Might be interesting to explore as a proof-of-concept for one or two selected apps. (BTW this is in response to your first comment; seems your second comment was posted at the exact same time as I was writing this one.)

@gewappnet I’m about to start the next phase of the mobile apps work, which will cover collection workflows. This will include how to download the installers outside the app store, and (tools for extracting) technical metadata. Once that’s done I’ll report the results in another blog post. I’ll also try to include iOS apps in this follow-up (even though AFAIK no good emulation options exist for that platform yet).

@bitsgalore I’m excited to here how all that goes, we’ll definitely be watching out for it to inform our work in EaaSI.

In regards to iOS: Corellium are doing iOS virtualization (emulation may take quite a bit longer as apple chips are bleeding edge and emulation always lags) and might be worth speaking with. They recently had a pretty good result in their court case with Apple.

@euanc Yes, my colleague @samalloing already brought Corellium to my attention. From their website I got the impression they were only offering a cloud based service, but the Arstechnica piece suggests otherwise? Anyway, it’s on my list of potential solutions to check out at some time.

I’d recommend reaching out to them. I’ve started a conversation in the past and they were receptive. Their technology is quite flexible also.

I just came across the new Waydroid project, which according to this piece is:

iOS emulation projects are actually starting now: https://emulation.gametechwiki.com/index.php/IOS_emulators Also see: https://emulation.gametechwiki.com/index.php/Cellphone_emulators